Todd Litman recently gave a talk at Transit 101 presentation hosted by 350Sacramento and others. There were some comments afterwards questioning some of what he had to say and his premises.

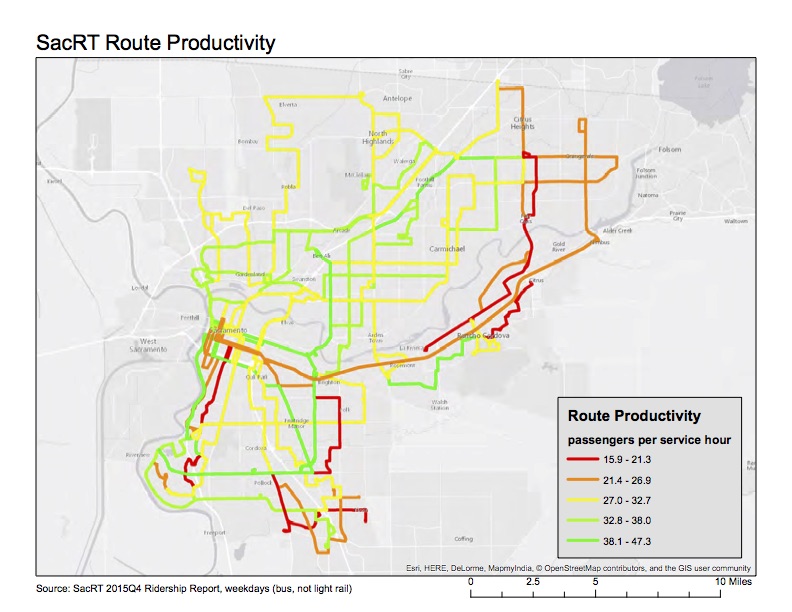

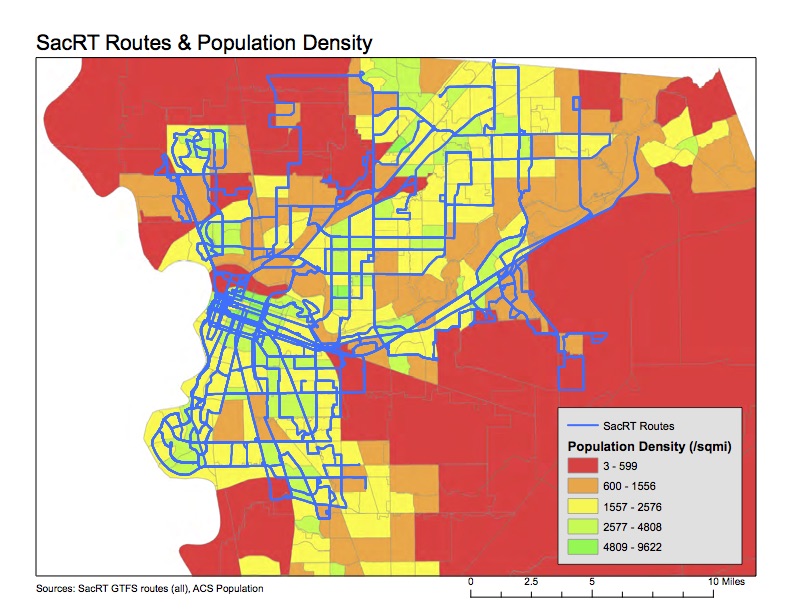

One of these was “He also ignores that the type of concentration he is advocating significantly increases the cost of housing.” Litman did present densification as one of the solutions to transit systems that are too spread out to function effectively, which is certainly one of the issues for SacRT.

If one looks only at the price of housing, the cost does usually increase as one moves from the suburbs towards the urban core. Though the pattern is actually much more complicated than that, with some inner-ring suburbs doing quite well while others are in steep decline. But the price of housing is only one aspect of living costs. The big, and often forgotten or dismissed, cost is transportation.

The key resource for exploring the tranportation aspects of housing affordability is the H+T Index (housing plus transportation) of the Center for Neighborhood Technology. To quote:

“By taking into account the cost of housing as well as the cost of transportation, H+T provides a more comprehensive understanding of the affordability of place. Dividing these costs by the representative income illustrates the cost burden of housing and transportation expenses placed on a typical household. While housing alone is traditionally deemed affordable when consuming no more than 30% of income, the H+T Index incorporates transportation costs—usually a household’s second-largest expense—to show that location-efficient places can be more livable and affordable.”

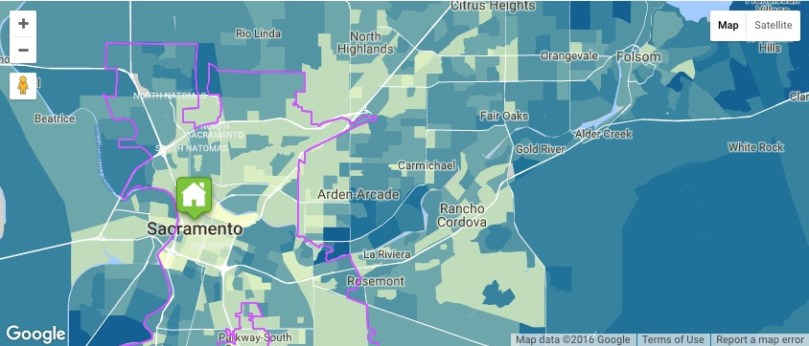

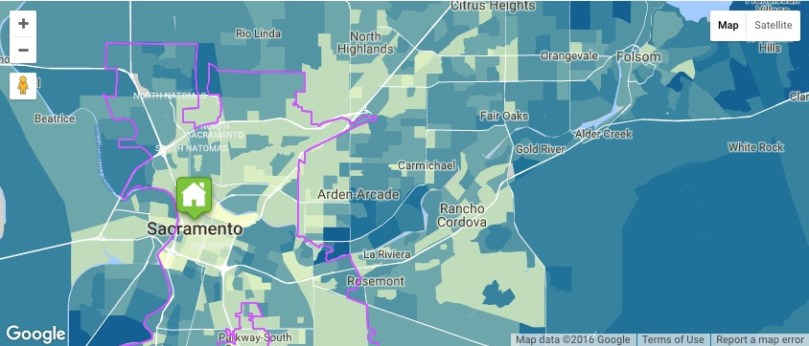

The map below shows the H+T index for a part of the Sacramento area. Light colors are affordable, dark colors are not. The general pattern is that housing becomes less affordable the further one goes from the urban core, though the pattern is of course complex. Part of Arden-Arcade is unaffordable both because housing is very expensive and it is a transit desert, while other parts are more affordable because housing is less expensive and it is not quite as much of a transit desert.

The devil is in the details, so I’d encourage you to explore the maps at CNT in more detail to see how this calulation works for specific areas, and how the H only (housing only) map compares to the H+T (housing plus transportation) map. I’ve written a bit about H+T before (Abogo), but it is always worth coming back to these very important concepts.

A lot of what people think about when they think about high costs in dense places are the really dense places, New York, Paris, San Francisco. However, the high costs of those places has as much to do with demand as with density. These places are expensive because so many people want to live there, and with limited housing options, competition drives prices up. In fact, the lower costs of suburban housing can be explained in large part by the far lower demand for such places. Not many people want the suburbs, so there is little competition for housing there, and prices stay lower. This is an oversimplification, but nevertheless true, and one of the perspectives that needs to be considered when looking at housing prices.

Another aspect of this misunderstanding is that many people envision densification as leading inevitably to very dense urban areas, which they associate with poor livability (though others seek out these dense areas), what are sometimes called inner cities, skyscrapers and tenements. Densification can mean intermediate densities, such as houses on smaller lots, multi-family housing, and buildings of moderate height up to five stories. Of course some people don’t like that either, but this is the minimum necessary for a functional transit system. The “new-traditional” format of houses on large suburban lots, or even worse, very large houses on very large exurban lots, cannot support a transit system. In the Sacramento area, midtown is an example of a moderate density place. It has single family homes, but also multi-family houses, apartment complexes, low-rise residential buildings, a good mix of housing types. And it is hardly dense at all, at least in my view.

Beyond the direct costs to the invidual homeowner/renter, however, are the costs we pay in sales tax and property tax, as well as fees, to build and maintain infrastructure. Infrastructure in less dense areas costs much more per household, or per square foot of floor space. Everything is longer in the suburbs: power lines, water lines, sewer lines, telephone/cable TV lines, roads, freeways, and most specifically distance to amenities. Everything. So far we have hidden that cost by having everyone pay equally for infrastructure, but if people were charged both for initial construction and maintenance by the amount of infrastructure per household or square foot, people who live in the suburbs would be paying much more for their services. As it should be. In fact, most of the suburbs are financially unsustainable since they can never generate enough sales tax, property tax, or fees to pay for what it really costs. That is in part why the suburbs are falling apart – there simply isn’t enough money to keep them going.

The cost of living in denser areas is less, the cost of living in less dense areas is more.