Continued from Part 1

Streets should be designed to induce traffic speeds that are appropriate to that street, consistent with surrounding uses. In my mind, that means 20 mph in residential areas and up to 30 mph in commercial areas. What about all those other roadways? They are mis-designed stroads. Properly designed streets:

- have a grid pattern so that use is spread out rather than concentrated on a few streets, so that intersections may functions without stop sign or signal control

- have good visibility at intersections

- have both physical constraints and visual clues to ensure that they are used at the intended speed

- have a minimum of signs

Of course that is largely not what we have now. What to do?

The solutions to an excess of stop signs are:

The solutions to an excess of stop signs are:

- Roundabouts, covered in my previous post What is a roundabout?

- Spread out traffic by installing traffic calming equally on parallel streets, rather than focusing traffic on select streets by installing traffic calming on other streets.

- Change intersections to increase visibility, by modification or removal or vegetation, fences, and parking.

- Replace four-way stops with two-way stops where there are sufficient gaps in traffic on the busier street.

- Replace both four-way and two-way stops with two-way yields, with the yield signs being on the lower traffic street.

- Remove all signs from low traffic streets, and allow vehicles normal yielding behavior at the intersection.

- Analyze all intersections over time to assess whether signing is really necessary, with the default assumption being that it is not.

I suspect that after analyzing intersections for the purpose of the stop sign, and alternate solutions, the number of stop signs would be reduced by at least 60%. Safety would not be reduced. Speeds would not increase. Both motor vehicle drivers and bicycle drivers would be happier.

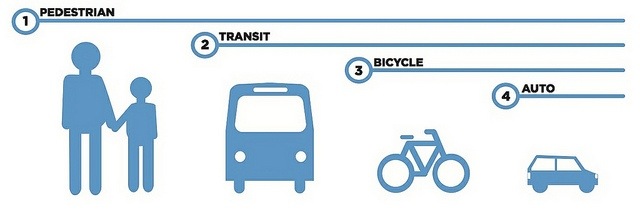

The chart at right shows the allocation to auto, walking, bicycling, and transit. It is based on the standard that sidewalks add about 3% to the cost of transportation project, and bicycle lanes add about 5%. Reading the project descriptions of the top 20 projects (out of 42 projects), I assigned a percent to ped and bike, and then calculated the project cost. I was pretty liberal, increasing the percentage for projects that actually had some purpose beside widening or extending streets, and only decreasing it when the project didn’t have any significant ped or bike component at all. Transit is even worse. The TPG doesn’t really even address transit, though it should. Transit is usually the best solution to congestion problems, yet it is never identified in the TPG as a solution. And in fact roadway projects can have a negative impact on transit when they clog areas that buses need to move freely, and place cars on top of light rail tracks.

The chart at right shows the allocation to auto, walking, bicycling, and transit. It is based on the standard that sidewalks add about 3% to the cost of transportation project, and bicycle lanes add about 5%. Reading the project descriptions of the top 20 projects (out of 42 projects), I assigned a percent to ped and bike, and then calculated the project cost. I was pretty liberal, increasing the percentage for projects that actually had some purpose beside widening or extending streets, and only decreasing it when the project didn’t have any significant ped or bike component at all. Transit is even worse. The TPG doesn’t really even address transit, though it should. Transit is usually the best solution to congestion problems, yet it is never identified in the TPG as a solution. And in fact roadway projects can have a negative impact on transit when they clog areas that buses need to move freely, and place cars on top of light rail tracks.