There are three ideas for transportation funding floating around, for the 2026 ballot, though none have been formalized. All rely on sales tax.

- Sacramento Transportation Authority (SacTA) may create a ballot measure to fund transportation. It would be in addition to the existing Measure A, and might fund transportation infrastructure for infill housing, which has not been done before. As an agency-sponsored measure, it would require 2/3 vote to pass.

- Sacramento Metro Rail and Transit Advocates (SMART) and Mayor Darrell Steinberg have drafted measure that would fund active transportation, transit, and housing. It would probably be for the county, but could be just for the City of Sacramento. As a citizen initiative, it would require only 50% + 1 to pass, a much more achievable vote.

- SacRT it considering a measure for transit and related active transportation that might cover only a part of Sacramento County, the more transit-supportive part, probably the cities of Sacramento and Elk Grove. As an agency-sponsored measure, it would require 2/3 vote to pass.

Sales taxes are regressive, meaning that low-income people pay a much larger percentage of their income to sales tax versus high-income people. Most organizations which lead with equity are opposed to further sales tax increases, feeling that enough is enough.

In Sacramento County, with a strong anti-tax voice in the low density unincorporated county, it is difficult though not impossible to reach the 2/3 threshold. The 2016 transportation sales tax fell short of 2/3. Measures to fund schools districts are more likely to pass. A complicating issue is that Elk Grove recently passed a sales tax measure to fund many purposes, one of which is transportation. Folsom and Rancho Cordova have sales taxes for which it isn’t clear to me whether any goes to transportation.

General purpose sales tax measures, which may list uses but are not required to follow those lists, only require 50% + 1 to pass. That flexibility is both a feature and a danger, since a government may shift sales tax income from what they said it would be spent on to other purposes.

Though I have not heard parcel taxes being discussed, they are another source of funding, though they are also regressive because they are a flat rate per parcel, not based on the value of the parcel.

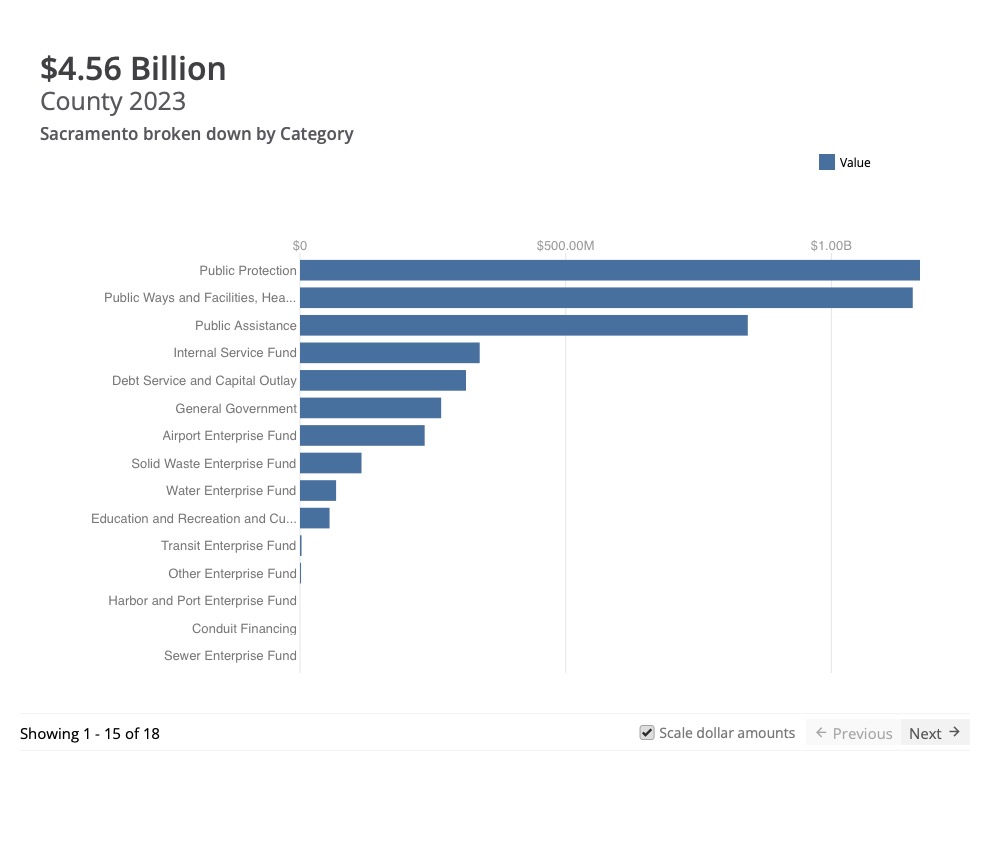

Two other types of tax which are progressive, meaning that high-income people pay a higher percentage of income than low-income people, are income tax and property tax. Income tax does fund transportation at the state level, but income taxes are not available to cities, counties, and special districts. Property tax can fund transportation, though due to Prop 13 which limits property tax, it mostly goes to schools and public safety. For Sacramento County in 2023, the chart below shows allocations. The ‘Public Ways and Facilities, Health, and Sanitation’ category goes mostly to Health, with Public Ways and Facilities being less than 20% of that category. This chart does not include school districts within the county, which also rely on property tax.

Transfer taxes, which are based on the value of a property when it is sold, are progressive. These have been discussed in a number of places in California, though not locally so far as I have heard. I am not aware of any existing transfer taxes that fund transportation, though they do fund a number of other government functions. The state levies a transfer tax throughout the state, and that income goes into the general fund.

Any county, city or special district can bond against property tax, meaning that they can expend money now and pay it back over time from future property tax income. Again, Prop 13 limits the usefulness of this by suppressing property tax income, but does not preclude it. If Prop 5 on the 2024 ballot passes, cities, counties, and special districts will be able pass bond measures with a 55% vote rather than 2/3 vote, though the proposition raises the bar on transparency and types of expenditures. Though Prop 5 is intended primarily to fund housing, it could fund transportation, and there is a logical nexus with transportation that supports housing.

For other posts on transportation funding, see category Transportation Funding.