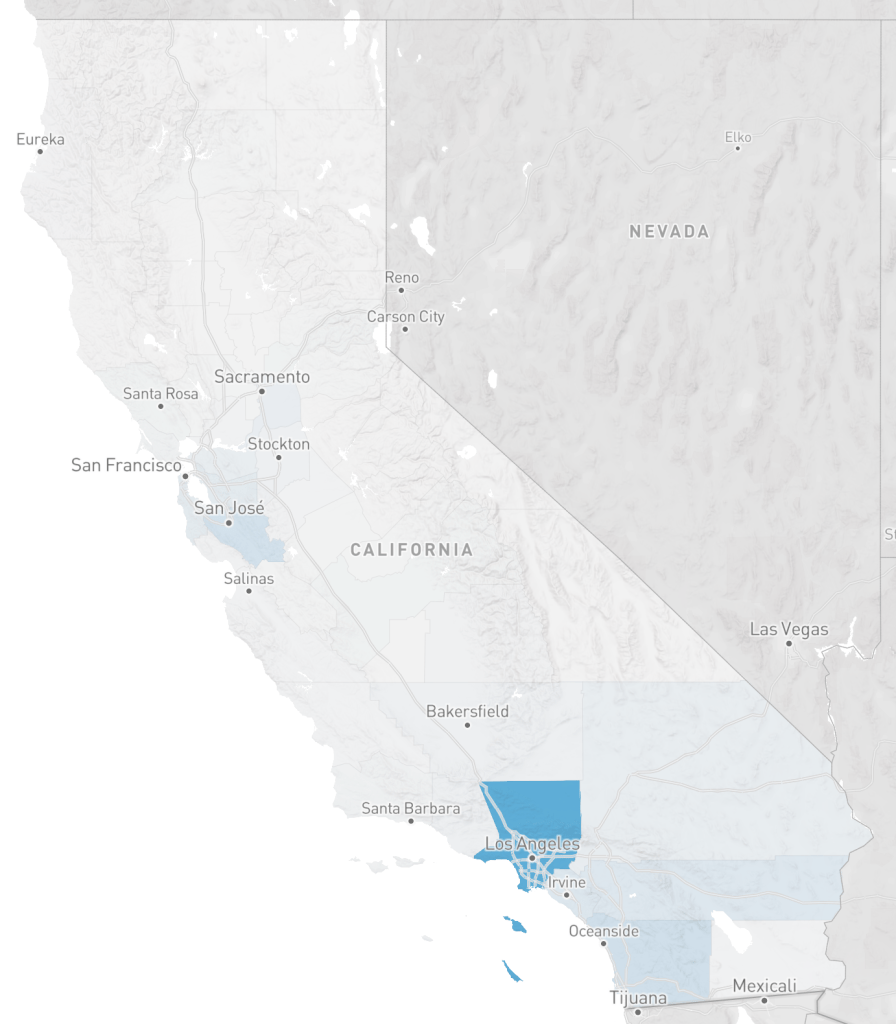

The City of Sacramento General Plan 2040 update draft offers a map of the SB 535 disadvantaged communities (DAC), on page 7-6, reproduced below. The areas are census tracts, and their number is labeled. Census tracts do not necessarily follow city boundaries, some overlap with county areas.

The general plan text states “Under SB 535, a DAC is defined as an area scoring in the top 25 percent (75th – 100th percentile) of all California census tracts for pollution burden and socioeconomic factors as measured in CalEnviroScreen.” You can read more detail about how DACs are determined, and the relationship to CalEnviroScreen, on page 7-3.

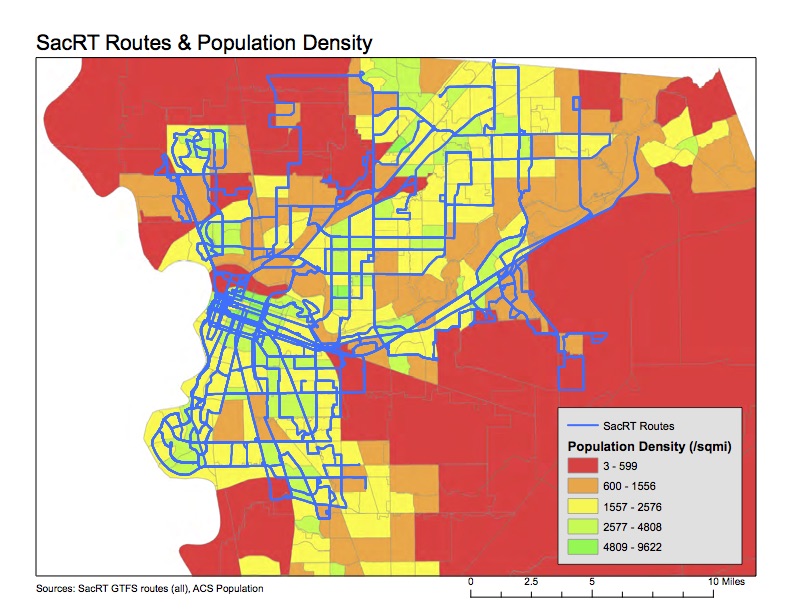

It is good that the area of ‘the finger’ (also known as the Fruitridge/Florin study area), disadvantaged communities in south Sacramento, are included, but it also makes the map hard to read. What areas are actually within the city, where the city might invest to overcome the past disinvestment that created these disadvantaged communities? To look at this question, I created the map below, which distinguishes city from county, blue being city and orange being county. It is clear that ignoring that significant areas of south Sacramento are in the county would be a mistake, but it is important to note where the city disadvantaged areas are, because that is where the city could spend money.

But these type of maps, where an area is mapped without reference to other characteristics, can be misleading. For example, the large area on the southeast side is indeed disadvantaged, but it is also mostly low density and even agricultural. The Census Bureau indicates that census tracts range between 1200 and 8000 people, with an average of 4000. Sacramento does not have such a wide range, but nevertheless, there are significant differences in the number of people residing in each census tract. The table ‘Table EJ-1: CalEnviroScreen Scores of DACs in the Planning Area’ (pages 7-4 & 7-5) lists the population density of all the tracts in the city, but unfortunately this data is not mapped. Of the disadvantaged census tracts, the population density (residents per acre) in the table range from 3.71 (6067006900, north area) to 20.71 (6067000700, northwest downtown)

So I developed a map that shows the range of densities (this is calculated for my map from area of census tract and population in 2022, not from the city’s table; the city does not indicate the date of the table data). A higher intensity of blue indicates more dense census tracts in the city, and for the county, a higher intensity of orange. As you can see, some of the city census tracts that are indicated as disadvantaged are very low density.

Why is density important? The city will never have enough money, from its own budget or other sources, to overcome past disinvestment. So investments must be prioritized. I believe the most important criteria is population density. A dollar of investment in a higher density area reaches more people. Conversely, investment in a low density area reaches fewer people. This fact is glossed over in the general plan.

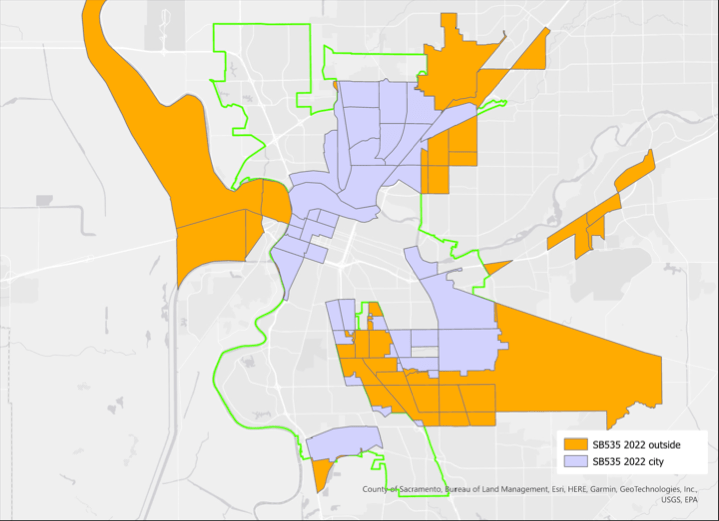

There are additional maps of the disadvantaged census tracts in the general plan, focused on particular areas of the city, and addressing such issues as healthy food resources, environmental justice issues, parks, and light rail transit. It should be noted that SB 535 disadvantaged communities are only one criteria for looking at an area. The state offers Low Income High Minority (LIHM), and SACOG uses that criteria among others. All of these criteria are important, but I believe density to be one of the most important.

You may comment on the General Plan under the ‘Self-Guided Workshop‘. For a good explanation of how to use this resource, see my previous post relaying the House Sacramento guide. For my earlier posts on the General Plan, see category: General Plan 2040.

PDF versions of the maps are available: SB 535 census tracts from General Plan; SB 535 city/county; SB 535 weighted for population density.