This post is a follow-on to three previous posts, in particular:

and many other posts on this blog (category Measure B) and on Sacramento Transit Advocates and Riders (categories Measure B 2016 and Measure A 2020).

It is quite possible that Sacramento Transportation Authority (SacTA) will decide to float a new transportation sales tax measure in 2022 or 2024. The transit, walking and bicycling advocacy community, which worked hard but largely unsuccessfully to improve the 2020 Measure A, which never made it to the ballot, will have to decide what to do between now and then. I argue that efforts to improve the newest measure will not significantly improve it because: 1) the SacTA board is resistant to including policy and performance goals in the measure; 2) the list of projects is and probably will always be a wish list of the engineers in each of the government transportation agencies in the county, which will always be weighted towards cars-first and ribbon cutting projects; and 3) SacTA gave strong lip service to the idea of maintenance (fix-it-first) in the measure, but there was nothing to guarantee that the expenditures would actually reflect that. One has only to look at the condition of our surface streets, sidewalks and bike lanes, and bus stops and light rail vehicles, to know that has never been the priority.

I would like to suggest three major alternatives to a new transportation sales tax measure put forward by SacTRA:

- a citizen-initiated measure that reflects the values of the residents and businesses of Sacramento County, and not the preferences of engineers

- a transit-only measure (with first/last mile walking and bicycling improvements), either for the county, or the actual service area of the transit agencies where residents support transit

- other sources of income rather than a regressive sales tax

Citizen-initiated Measure

A citizen-initiated funding measure only needs to pass by 50%+1, whereas agency-initiated measures need to pass by 2/3. The 2/3 level is hard though not impossible to achieve – several transportation and transit measures in California have achieved that level, but certainly 50% is easier. This 50% is not based on a specific state law, but on a court ruling about San Francisco’s tax measures which passed with more than 50%. It will probably be subject to further court cases as anti-tax organizations try to overturn the ruling, but for now, it stands. The 2016 Measure B had a yes vote of 64%+, but needed 2/3, and therefore failed. The polling done for the 2020 Measure A was also less than 2/3, which is why Sacramento County and SacTA declined to put it on the ballot.

I have no illusions about how difficult it would be to engage the community, write a ballot measure, and then promote it strongly enough to receive a 50% plus vote. The recent experience the community organizations that supported a measure for stronger rent stabilization and eviction protection in the City of Sacramento, that failed to pass, gives pause. The SacMoves coalition spent thousands of hours of individual and organization time, basically writing a good measure for SacTA to use, but very little of that effort was included in the measure proposed by SacTA. A successful citizen-initiated measure would require more than double the amount of work, and a broader coalition. Nevertheless, it is an option that I think should receive serious consideration.

I doubt that the structure of SacTA, which is board members that are elected in each of the jurisdictions, without formal citizen or organization representation on the board, combined with a Transportation Expenditure Plan that is and will alway be a wish list for roadway engineers, can ever lead to a good measure. We could of course wait to see what SacTA comes up with, or again try the largely unsuccessful attempt to improve the measure, or just oppose any measure from SacTA.

Transit-Only Measure

The percentage of 2020 Measure A allocated to transit was actually lower than in the 2016 Measure B, and lower than in the existing Measure A. Some of the difference in 2020 was due to the regional rail allocation being subtracted from the transit allocation, but there was more to it than just that. Sadly, SacRT accepted this reduction as ‘the best they could get’. To citizen advocates, though, it was unacceptable. Since the 2020 measure was not placed on the ballot, it was not necessary for advocates to formally oppose passage of the measure, but I believe most of them would have.

A transit-only measure would avoid this competition between maintenance, roadway capacity expansion, and transit (notice that walking and bicycling are not really in the competition at all), by allocating all funds to transit and related needs. The amount of course would not be the half-cent sales tax of the 2020 Measure A, but more likely a quarter-cent sales tax (or equivalent in other incomes sources, see the next section). Certainly the advocacy community would support first/last mile walking and bicycling improvements in the measure, though I’m not sure exactly how it would be defined or whether the percentage would be specified ahead of time.

A transit-only measure would more easily allow the SacRT to determine how much to allocate to capital (bus and light rail vehicles and rail, and related items such as bus stops and sidewalks) versus operations, and to change that allocation over time as needs changed. The three counties that are members of Caltrain passed 2020 Measure RR for a eighth-cent sales tax to fund operations, with 69% of the vote, and at least 2/3 in each county, precedence in California for transit-only measures.

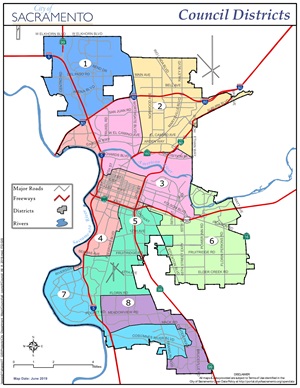

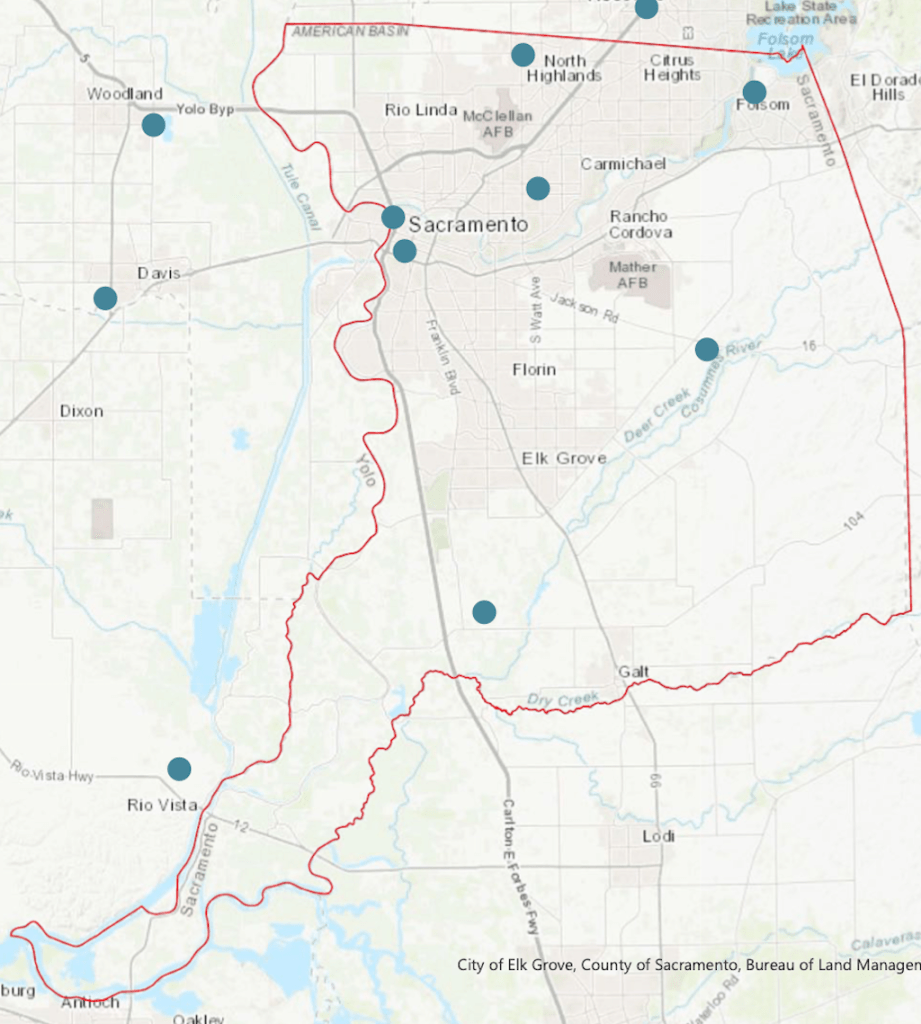

For a transit-only measure, a decision would have to be made about the geographical area it covers. Sacramento County, only and exactly, or Sacramento County plus the YoloBus service area, or just the transit-using areas. It was clear that the strongest support for 2016 Measure B was in the transit-using parts of Sacramento County, and if these areas were the only ones, it would have passed easily. There has also been a lot of opposition to transit expenditures on the part of the county supervisors who say they represent the rural and semi-rural areas of the county (it is statistically impossible that three of the five supervisors represent rural, given that the population of the county is mostly urban and denser suburban). A lot of advocates then said, well, if they don’t want transit, then let’s exclude voters and their tax income in the future. Of course the projects defined in the measure, mostly capacity expansion, could not be funded off sales tax from only the rural and semi-rural areas, so most of these would never happen. And I think that is a good thing.

Other Sources

The sales tax rate in Sacramento County is 7.75%, and ranges up to 8.75% in the City of Sacramento and some other locations. I am not opposed to sales tax, but I think we are at or close to the point of diminishing returns on sales tax income versus impact on people and businesses. Sales taxes are regressive, in that lower income people pay a much higher percentage of their income for sales tax than do higher income people. It is not the most regressive of taxes, that award probably goes to flat rate parcel taxes where people with a lot of land and expensive buildings pay the same as anyone else. For more detail on possible funding sources, please see my earlier post: transportation funding ideas.

California under Prop 13 has an intentionally biased tax base, where property tax depends more on when you purchased than on the value of the property. I really hoped that 2020 Prop 15 would pass, undoing part of the tremendous damage that Prop 13 has done to California, but it did not. So while small and gradual increases in property tax income can occur, it is probably not enough to finance our transportation system. This saddens me, because I believe property tax would be the best, most equitable source of funding.

If property tax can serve only part of the need, and further sales tax increases are not my preference, what then? First, I think that both federal and state funding of transportation should move away from any and all roadway capacity expansion. Overall federal and state transportation funding should be greatly reduced so that it only funds needs that are more than county or regional level. And yes, federal and state taxes should be commensurately reduced, so that the money does not simply go elsewhere. State prohibitions on the type of taxes and fees that can be levied at the city and county level should be mostly or entirely removed, so that cities and counties can then recover the foregone state and federal taxes for whatever transportation uses they deem.

Local transportation needs would still exist, and should be locally funded. Yes, I want Sacramento County to provide most of the transportation funding for Sacramento County. It is necessary that local people pay for transportation, and see the benefit of what they pay for, so that they can make rational decisions about what they want and how to pay for it. Getting state and federal grants to meet local transportation needs is just a game that agencies play, hoping that they will somehow get more than they give. We know that states with strong economies, such as California, subsidize transportation in other places, and that regions with strong economies such as Los Angeles area, Bay Area, and maybe Sacramento, subsidize transportation in other regions. No reason for that to be happening, unless the need being addressed is regional or greater. If you don’t agree on this, I’d ask that you read Strong Towns Rational Response #1: Stop and Rational Response #1: What it means to STOP. And everything else by Strong Towns, for that matter.

We have spent trillions of dollars on a motor vehicle transportation system, with the biggest accomplishment being destruction of communities of color, impoverished economies and communities, pollution-caused health problems, climate change, and death, injury, and intimidation of walkers and bicyclists. It is time to stop. All future funding should go to maintenance, transit, intercity trains, walking, and bicycling. Those who want to bring ‘balance’ by making a small shift are asking that we continue the madness. We should not.

Examples of projects or maintenance that should come from the state or federal level? The Interstate highways that are actually dedicated to national defense and interstate commerce. In Sacramento region, that means Interstate 5 and Interstate 80. No, not the current freeways that have been bloated to serve local and regional commuters, but the highways. Two lanes in each direction would be sufficient to meet the legitimate needs of these highways. All additional lanes, if any, should be completely funded at the local level because they serve local needs. Long distance and regional rail should also be funded. In the case of Sacramento, that means the Amtrak Coast Starlight and California Zephyr, and the Capitol Corridor and San Joaquins regional rail. That’s pretty much it. There might be some argument for funding freight rail infrastructure and maintenance, not sure. No, I don’t think airports should be funded at the any level, they are a transportation mode that benefits primarily high income travelers and shipping corporations. If they want that infrastructure, they should pay for it.

So, how to fund transportation in the county?

First, charge for parking everywhere, even in residential areas. A residential parking permit should reflect the part cost of maintaining all streets. Quite possibly, people would reduce their use of the public street to store their personal vehicle, and might reduce their ownership of vehicles so that they don’t need to park on the street, and those would be good side effects, but would also limit the income from those permits. When there are fewer vehicles parked, there is less resistance to re-allocating space to sidewalks, sidewalk buffers, and bike lanes. Metered parking should be raised to ‘market rates’ which means what it would cost to park in a private garage or lot, AND achieves the Shoupian ideal of at least one open parking space on every block. Of course all parking revenue should go to transportation, not to other uses (such as paying off the Golden 1 Center). The Pasadena model of using some parking income to improve the street and surrounding areas is compatible.

Second, charge for entry into congested areas. In Sacramento County, that would primarily mean the central city. The purpose of this fee is not to reduce congestion, though the fees are often called congestion fees, but to obtain the income necessary to build and maintain our transportation network. The fee would be for each entry, so that people who live in the central city but don’t use their car much would not be paying a lot, while people who commute into the central city for their own convenience would be paying a lot.

These two sources alone might well not meet the need for transportation funding in the county, and I don’t have a ready solution to that. I don’t want development impact fees to go to transportation because I think they should be used to upgrade utilities and fund affordable housing. Same with title transfer taxes.

So, those are my thoughts of the moment. Comments and other or additional ideas are welcome.