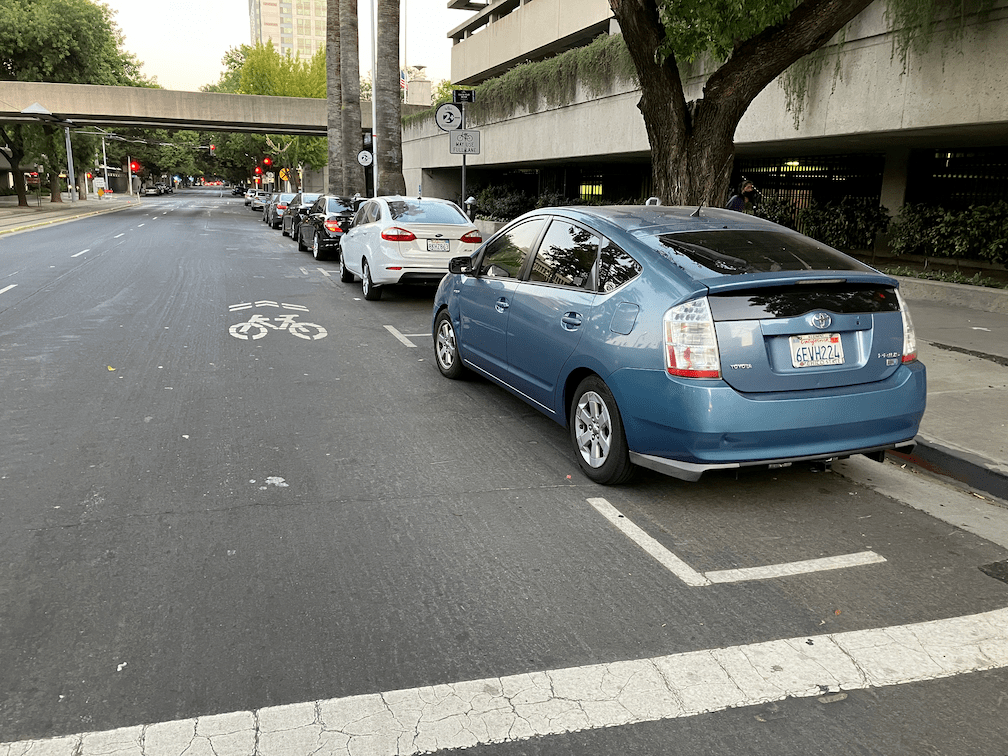

My last three posts have been about locations where sharrows replace bike lanes for one-block sections in the Sacramento central city: Sacramento’s worst possible place for sharrows; Sac kill those sharrows on I St; Sac kill those sharrows on H St. There may well be other such locations that did not come to mind. If so, please let me know so I can document and post on them. I’m not asking about locations that should have bike lanes, or where bike lanes should be upgraded to separated (protected) bikeways. There are simply too many of those locations for me to deal with.

So, why are bike lane gaps so important? Bike lanes are basically a promise to bicyclists that the city is providing a safe place to ride your bike. Yes, I know traditional bike lanes have serious safety issues (they are called door zone bike lanes, or DZBLs), but for the average rider, they are safer than no bike lane. But this promise is broken when there is a gap. For these gap sections, bicyclists who felt comfortable riding in a bike lane are suddenly left to deal with motor vehicle traffic in a location where neither the bicyclist nor drivers are sure how to behave. What does the average bicyclist then do? Decide never to ride on that street again. And if they have a scary experience, they may even decide not to ride again at all.

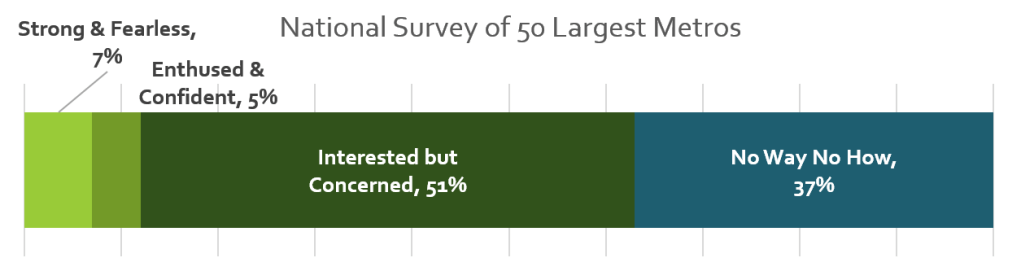

I’m a bicyclist with strong vehicular bicycling skills. I know where the safest place to ride is on every street, and I ride there no matter what motor vehicle drivers or law enforcement happens to think about it. But I am far, far from a typical Sacramento bicyclist. I am ‘strong and fearless’, though as I get older, I’m tending towards ‘enthused and confident’. The four types of bicyclists, or levels of comfort, developed in Portland but applicable to Sacramento, are shown in the graphic:

The city should be designing bicycle facilities that work for all three categories of people who will bicycle. When there is a gap in a bike lane, the city has designed bicycle facilities that serve the ‘strong and fearless’, only 7% of potential bike riders. This is discriminatory. It is wrong. I suspect that with the resurgence of bicycling and the availability of e-bikes, the ‘no way, no how’ category has shrunk a bit.

The city must close bike lane gaps. Not off in the future when the street is repaved, or when a grant is obtained, but NOW. To do otherwise is to intentionally discourage bicycling and to risk people’s lives.